by Sebastian Faust

Wanna see my picture on the cover

Wanna buy five copies for my mother

Wanna see my smiling face

On the cover of the Rolling Stone

– Dr. Hook & The Medicine Show, "The Cover of the Rolling Stone"

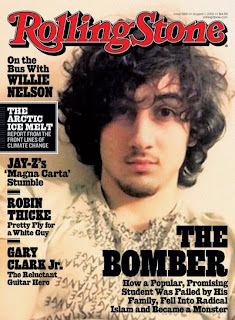

Rolling Stone is facing blowback for their latest issue’s cover – a self shot of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the two brothers alleged to have committed the Boston Marathon bombing. Tsarnaev addresses the camera, looking out at us as a young indie-rock singer/songwriter might; he’s got long, tousled hair, scruffy whiskers, a graphitied white shirt, and dark, piercing eyes. He looks hip. He looks cute. He looks nice. And that’s the problem.

The outcry was swift. The mayor of Boston issued an open letter decrying Rolling Stone’s “celebrity treatment” of Tsarnaev, arguing that the survivors of the Boston bombing deserve their own cover stories, but that he no longer feels that “Rolling Stone deserves them” (emphasis mine). Twitter blew up with responses to the cover. Boycotts have been announced by CVS, Walgreens, Rite-Aid, Kmart.

Every post on Rolling Stone’s Facebook page, from a poll about the best Ramones song to a rundown of Louis C.K.’s performances, is plastered with obscenity-laden replies about the soon-to-be-released cover. Most of them simply spew invective at the magazine, but some cut to what, I think, is the actual issue underlying the anger people feel. These say, essentially, “This picture of the suspect is too flattering; if you were going to place him on the cover at all, you should have used his mug shot.”

Tsarnaev looks good. And that’s the problem.

It’s not as if magazines haven’t featured other “monsters” on their covers before. In 1970, Rolling Stone itself ran with a picture of mass murderer Charles Manson; in 2001, TIME devoted their cover to Osama bin Laden. But the difference is in the aesthetics of the pictures. Manson’s photo was shaded by a yellow circle overlapping his face, save the whites of his eyes, which gave him a manic look. Bin Laden wore a turban and a Middle-Eastern beard; he looked unusual to Americans. He looked foreign, alien, other.

It’s not as if magazines haven’t featured other “monsters” on their covers before. In 1970, Rolling Stone itself ran with a picture of mass murderer Charles Manson; in 2001, TIME devoted their cover to Osama bin Laden. But the difference is in the aesthetics of the pictures. Manson’s photo was shaded by a yellow circle overlapping his face, save the whites of his eyes, which gave him a manic look. Bin Laden wore a turban and a Middle-Eastern beard; he looked unusual to Americans. He looked foreign, alien, other.But Tsarnaev looks like us. And that’s the problem.

We have decided that Tsarnaev is evil (the posts I referenced earlier on Rolling Stone’s Facebook page are filled with sadistic descriptions of his hoped-for demise), and so we want him to look the part. Evil is ugly. It is disfigured, or alien, or just a little bit off. Our villains need to wear capes, or turbans, or pencil mustaches, or terrorist beards. They need to be crazed, or mad, or so full of hate that we can never hope to understand them.

They need to have defining characteristics, so we can pick them out of a crowd. Then we won’t have to worry. We know the man with shifty eyes isn’t to be trusted. But above all (and we must be adamant about this) they need to most definitely not look like us, like people we know, or like a “rock star.”

We know what evil looks like. And it doesn’t look like us.

My guess is that most of those who are outraged didn’t take the time to read the article. My guess is many didn’t even take the time to read its title, right there on the cover: “The Bomber: How a Popular, Promising Student Was Failed by His Family, Fell Into Radical Islam, and Became a Monster.”

Or maybe they did; maybe that’s the problem. The point of the picture paired with the article was to question how someone who looks like “us” could become one of “them,” to show that it isn’t such a great leap. But that isn’t a narrative we want to hear.

We want to hear that terrorists are born in far-flung countries and bred in desert camps. We want to hear that they have an ideology that makes no sense, that is incomprehensible to us, that we can never wrap our heads around and understand. That they hate us for our freedom, or for being powerful, or for being “special.” But in the case of Tsarnaev, that narrative proves untenable. Though foreign-born, he was a product of our schools, of our culture, of our society. He not only looks like one of us in that picture, he was one of us. He is one of us.

We want to hear that terrorists are born in far-flung countries and bred in desert camps. We want to hear that they have an ideology that makes no sense, that is incomprehensible to us, that we can never wrap our heads around and understand. That they hate us for our freedom, or for being powerful, or for being “special.” But in the case of Tsarnaev, that narrative proves untenable. Though foreign-born, he was a product of our schools, of our culture, of our society. He not only looks like one of us in that picture, he was one of us. He is one of us.Evil is always a monster. It’s always outside of us, stalking the night, clawing our windows, rattling our doors. It haunts us in dreams. It can only be frightened away, or warded off. Or killed.

Evil is always a monster. It can’t be reasoned with, or listened to, or understood. It can’t be touched. It is something with which we can never bridge the gap, with which we can never become familiar.

Because the moment we recognize it as familiar, it is something with which we can empathize. And if we can empathize with something, we can forgive it. And if we can forgive something, we can love it.

But we can’t love a monster. We can’t forgive one either.

Sebastian Faust is an avowed heretic, armchair theologian, and a self-styled canary in the coal mine of pop culture. He takes life by the reins, bulls by the horns, and tigers by the tail, all while living in Nashville. You can't follow Sebastian on Twitter because he doesn't understand technology.

You can, however, follow On Pop Theology on Twitter @OnPopTheology or like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/

You might also like:

No comments:

Post a Comment