by Ben Howard

Every once in awhile I listen to this podcast called

Hardcore History. It only comes out every few months, but when it does the

episodes are often 3 or 4 hours long. I was a history major in college, so this

kind of long, audiobook-like podcast is perfect for me.

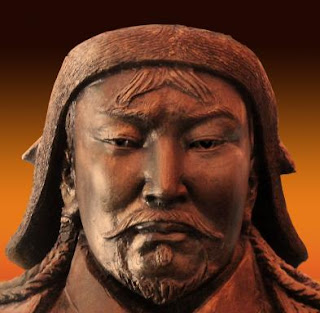

Yesterday, I found myself listening to an episode about

Genghis Khan. A lot of modern historians credit Genghis Khan with connecting

China and other Asian societies with the European continent in the 13th

century. In the aftermath of Genghis Khan’s conquest there were great advances

in commerce and trade and technology that would not have been possible without

the Khan.

This is the accepted historical significance of Genghis

Khan. At some point historians will eventually mention, almost as an

afterthought, that during the Khan’s 20 year reign he was responsible for the

death of between 10 and 80 million people.

You read that right. 10 to 80 million deaths and it’s not

the most important thing according to his historical legacy.

We read that, or at least I read that, and think that things

must have been horrible back then. Such utter decimation is a travesty, a

shocking tale of the reckless warlike past of the human race. To be honest,

really honest, we think we’ve advanced beyond that. We’ve progressed and grown

and civilized.

Yet 70 years ago, there was a war between all the

progressive, civilized, mature countries that had clearly advanced beyond the

barbarism of someone like Genghis Khan. And during the course of this war,

which lasted just 6 years compared to the 20 during which the Khan reigned, 50

to 70 million people were killed.

I hear it said from time to time, often crediting Martin

Luther King Jr., that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends

toward justice.

Though the sentiment is beautiful, I cannot say with

confidence that the universe bends towards justice. Neither can I say that it

builds towards progress. I cannot say, with any confidence that the world today

is better than it was yesterday or that it will be better tomorrow than it is

today. I want to, but there are times when even lovely things, even beautiful

things, just aren’t true.

Justice is such a fleeting thing, such an elusive and fickle

mistress for us to pursue. Derrida argues that justice is the only thing that

we cannot deconstruct, the only thing that we cannot get behind, or beyond, or

underneath, or inside of, it is entirely its own. As a result, it is always an

illusion and always out of reach.

The simple fact is that even if we cure all of the

injustices found in the world today, even if we create a just society where

everyone is treated equally and loved and no one goes wanting or needing,

tomorrow we will wake up to find new injustices that we never knew existed

tucked away in shadows where we had never before looked.

Regardless of what we do, regardless of captives we set free

from bondage, the hungry to whom we give food, and the thirsty to whom we give

drink, in the cold, harsh light of history our children and our children’s

children will look back, shake their heads and say, “How could they have done

THAT?”

And we will say that we did not know.

This is not a condemnation. It’s not a tragedy that humanity

falls victim to the pitfalls of being trapped in space and time, it just…is.

This is also not my way of mocking those who work so ardently for justice. What

they do, what we all do, is good and pure and righteous, but it will never be

done.

Today, many people across the world are observing Holocaust

Remembrance Day. I hope that you will join them, and I hope that along with

those who lost their lives during that terrible time, you will also remember

the victims of all injustice past, present, and future; those you have known

and those you have never met; those you have aided and those you have

unknowingly oppressed.

Perhaps the moral universe does not bend towards justice,

but it does bend toward hope. And faith. And love.

Perhaps the moral universe does not bend towards justice,

but it does bend toward hope. And faith. And love.

And the greatest of these is love.

Peace,

Ben

Ben

Howard is an accidental iconoclast and generally curious individual

living in Nashville, Tennessee. He is also the editor-in-chief of On Pop

Theology and an avid fan of waving at strangers for no reason. You can

follow him on Twitter @BenHoward87.

You can follow On Pop Theology on Twitter @OnPopTheology or like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/OnPopTheology.

You can follow On Pop Theology on Twitter @OnPopTheology or like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/OnPopTheology.

You might also like:

Can we say that the sentiment is GOOD, and that it becomes our job to try to make it TRUE? In the end, I believe it will be God's work. But, I still believe it will occur. It is up to us to get on board, and to try to bend the arc in the right direction. That's all for now -- I have my afternoon windmill-tilting to complete.

ReplyDeleteYes, the sentiment is certainly good. In my head I probably conflate beauty with goodness. And I do think it's our job to make it true.

DeleteThat said, even our conceptions of justice are constructs. We talk about justice in the present in terms of rights, which are a philosophical invention. It would only follow that a rights-based conception of justice is an invention as well.

I think a pursuit of justice is always good, and I think in the end it is left to God's work. Our pursuit is to constantly try and uncover the thing behind the thing, and work towards justice even if it is unachievable.