|

| That's all folks. |

Yesterday I was reading through a blog post where the author had collected a bunch of articles about Game of Thrones and theology. A few dealt with the issue of morality in the universe created by George R.R. Martin. They made arguments about what the story meant.

The author of the post responded to one of these articles by saying that, "We can't yet say what the story means because we do not yet know how the story ends."

This phrase struck me in the moment and has stayed with me since. It fascinates me because while it's true, I'm not convinced that it should be.

At their very root, stories are constructs. They are snippets lifted from an ever-evolving, ever-unwinding narrative. We give them a beginning to provide context and an end to provide meaning, but the reality is that the meaning we impose is defined by where we begin and end the story.

Take for example the story of Johnny Cash told in Walk the Line. The story told in the movie ends with Johnny marrying June as the climactic moment in a story of love and redemption. The end of the story re-defines the meaning of Johnny's experiences as an unloved child, his rise to fame, his drug problem, and his unsuccessful first marriage. The story is cast in the light of its conclusion.

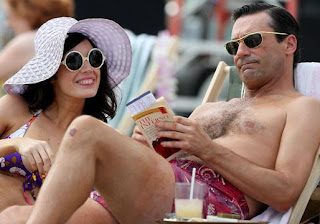

|

| Happily ever after? |

So what does a story mean if a story never ends?

To judge something by its end means that you have to choose. Either you can cut off the story and choose to say, "This is what this story means now, in this particular moment," or you can let it play out delaying ultimate judgment eternally because even in death, the ripples never cease. The consequences and effects of a life lived and a story told intermingle with the ripples of other stories and other lives and continue forward, gently fading into one.

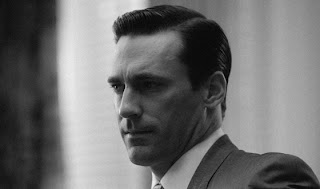

The question of whether meaning is tied to an ending is an interesting one to consider now when the world of pop culture, especially TV, stands on the brink of so many of these "important" endings. Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy ended last year. Mad Men is in it's next to last season. Breaking Bad is approaching it's final year. Even the prolonged (and occasionally frustrating) narrative of How I Met Your Mother is beginning it's final season in the fall.

Is the entire meaning and essence of these stories tied into their end? If Don dies, or Walter goes to prison, or if Ted meets "the mother" and she's terrible, does it ruin what came before it? What about the story that comes after it, the fictional narrative that we'll never see play out?

|

| Worst movie, or worstest movie? |

Most Christian theology defines itself in terms of its end. That's not just true for people who believe in the rapture, or an eternity spent in a heaven/hell removed from this world, but for those of us who believe in the second coming and the restoration of creation. So many of us define ourselves by the hoped for outcome at the end of the story, but what if this myopic focus blinds us to the beauty of everything else?

What if the end, and the beginning too for that matter, aren't actually real? What if they're constructs we use to delineate and divide life into consumable chunks? And if that's true, what does it mean when we use them to explain the parts in between?

What if stories don't end? What if life keeps going on? What does it mean then?

Peace,

Ben

Ben Howard is an accidental iconoclast and generally curious individual living in Nashville, Tennessee. He is also the editor-in-chief of On Pop Theology and an avid fan of waving at strangers for no reason. You can follow him on Twitter @BenHoward87.

You can follow On Pop Theology on Twitter @OnPopTheology or like us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/OnPopTheology.

You might also like: